Why Genesis Started Writing Shorter Songs: Exclusive Interview

As the '80s dawned, Genesis began releasing more concise, radio-friendly singles. It seemed, at least to the casual listener, that this shift coincided with Phil Collins' ascension after the exit of founding singer Peter Gabriel.

In truth, Genesis had been dabbling with tender (and shorter) balladry as far back as "More Fool Me," from 1973's Selling England by the Pound – well before Gabriel went solo. At the same time, Genesis didn't completely eliminate lengthier explorations, even in the '80s.

Keyboardist Tony Banks has since returned to long-form pieces, completing a new classical-themed album titled Five. He joined us to discuss Genesis' attempts to balance these two competing impulses, while dealing with the perception that they'd left progressive rock behind in the '70s.

You guys naturally evolved into more commercial-oriented pieces, though you also usually included one or two lengthier pieces, like "Domino." Was there a part of you back then, particularly in the '80s, that would have preferred to explore more progressive material?

I really enjoyed for many years writing longer pieces. We just got to a stage where we wanted to do it a bit differently. I came into the business loving pop music in the '60s, which was all concise. I love the Beach Boys, the Beatles, the Kinks, the Zombies – a little bit more imaginative but still concise songs. When we found we could do it, which is something we didn't know we could do, it became very exciting – and I really enjoyed doing that. I tend to look at our whole body of work, if you like, and it's all in there. When one thing happened or when another happened [isn't important]. We've got lots of short songs, long songs – there are songs like "Domino," "Tonight Tonight Tonight," "Home By the Sea" that have more than one facet to them. When you get it really right with a short song, like "Land of Confusion" or "Follow You, Follow Me," I'm really proud of those songs because there's something about them. I didn't know we could actually do that; it was an exciting thing to do. We also all had our solo albums, so on some of mine, I went a bit more extravagant and had some longer pieces like "An Island in the Darkness," which is 17 minutes long. I was able to get that out of my system a bit, really. It was fun doing it both ways. But these days, I suppose I'm back into the longer pieces, but doing it with orchestras.

Listen to Genesis Perform 'Domino'

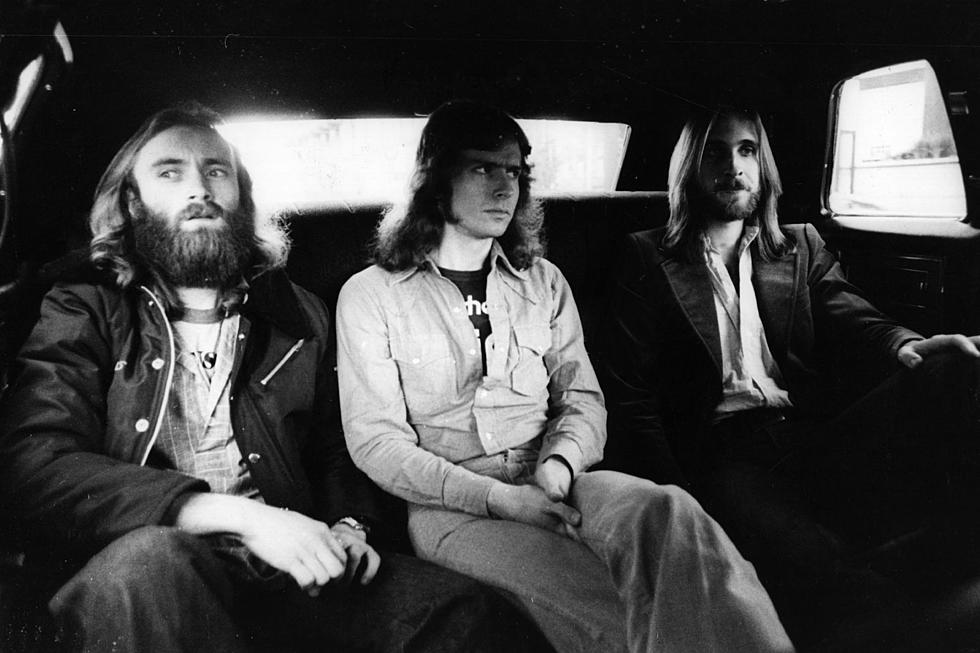

During Genesis' trio era, you guys eventually worked out an effective system where you'd all enter the process with a blank slate and rely on jamming. The songs would evolve organically from there.

I think that's why the songs ended up a little simpler in many ways, because the three of us were there together without any ideas coming in. For things to work when you're playing together, you need a slightly more concise approach. More simplicity was necessary. We tried to catch ideas quickly on those last three albums we did with Phil, instead of laboring them and working them – which we'd done in the early days, which I like as well. We sometimes tried to leave a song almost how we first came across it, keep it as simple as possible. With things like "No Son of Mine" and "Driving the Last Spike," it was almost like we had the chord sequence I played and Phil sang a little line on top of it, and we said, "Well, that sounds really nice. Let's just leave that and build from there instead of hammering out something more exotic, like we would have done in the early days." It was an interesting way of working, almost like three people working as one. We had a good way of working: We all had our roles, I suppose, and there was very little conflict, and a lot of great results.

Your contributions have often been overshadowed by dynamic frontmen like Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins. Is one of the reasons you like working in the orchestral realm because you get more respect as a songwriter?

Not particularly. In many ways, I'd love to have a Peter of a Phil with me now because they'd be doing the promotion, and that's the side I've always found rather difficult. It's nice, I suppose, for it to be known that you've written it all. Back in the old days, we had collaborative writing credits, and the degree of which people were involved on some songs were very different from others. "Firth of Fifth," which I suppose compositionally was all mine, was [credited as] a group song. Other times, my contribution might have been quite small, but I still got the credit. We decided in the early days of Genesis that we wanted to try it like that. We all felt close to every song, and you weren't trying to push your own song all the time because you got the credit. So, that worked okay. I think sometimes it meant the contributions, particularly from Peter in the early days, were slightly given more credit than they should have. He's a great composer, and he's written some fantastic stuff, but because he was the singer, people tended to think he did more than he really did, I think. I don't have a problem with that really. Over the years, I'm glad to have been a part of that. And the writing relationship was very collaborative, so it represented what we actually did.

See Genesis Among the Top 100 Albums of the '80s

More From 96.9 WOUR